In September 1922, Swedish filmgoers settled in for the most expensive Scandinavian film of the era: Häxan, later known as Witchcraft Through the Ages.

At the Stockholm premiere, audiences enjoyed a live orchestra and illustrated playbills introducing the film’s cast and creative process. This level of pomp and circumstance was typical for high-profile European movies at the time. Less typical was Häxan’s accompanying bibliography, citing dozens of academic sources ranging from medieval religious texts to Jungian psychoanalysis. It was an early hint that this wouldn’t be a normal night at the movies.

Arriving four years before the word “documentary” was first used to describe a film, Häxan introduced a new mode of storytelling. Shifting between illustrated lectures and dramatic vignettes, director Benjamin Christensen presented a seven-chapter treatise on medieval witchcraft, reveling in lurid scenes of dark magic and religious torment.

Opening with a slideshow exploring historic beliefs in magic, Häxan then plunges into a nightmare of paranoid superstition. Wizened crones stir potions in gloomy dungeons. Demons caper and cackle. Nubile satanists cavort in midnight rituals. Fervent clergymen persecute innocent women for nonexistent crimes. Christensen even demonstrates some medieval torture instruments.

Following this cavalcade of horrors, the director presents his final thesis, connecting the symptoms of witchcraft with contemporary images of mental illness. “The little woman whom we call hysterical, alone and unhappy, isn’t she still a riddle to us?” he asks.

Influenced by the work of Freud and Jung, he sought a scientific explanation for an archaic social phenomenon. Some viewers welcomed Häxan on these terms. Others did not. Thanks to its blasphemous content, nudity, and sadomasochistic undertones, American censors banned the film outright. Even in Sweden, the premiere’s 91-minute cut judiciously trimmed the edgier scenes, running shorter than Criterion’s recently released 105-minute restoration.

“He had aspirations to produce a very truthful, scientifically sound document of the witch craze,” says Edinburgh University professor Richard Baxstrom, coauthor of Realizing the Witch, a book exploring Häxan’s academic roots. “He was incredibly intelligent, very driven, and a little bit nuts.”

MGM studio boss Louis B. Mayer voiced a similar opinion after watching Häxan in 1924, asking “Is that man crazy or a genius?” Evidently Christensen’s talent outweighed his eccentricity, because Mayer soon signed him to his first Hollywood contact. This conflicted fascination exemplifies Häxan’s lingering appeal; a singular product of a singular mind.

Born in Denmark in 1879, Christensen initially went to medical school, overlapping with followers of the neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot, who taught Freud and shaped the 19th-century concept of hysteria.

But Christensen wasn’t destined for medicine. After dropping out of university, he trained as an opera singer but moved on to stage acting and then to the champagne trade, returning to performance during Denmark’s silent film boom in the early 1910s. Soon he was making his own movies, directing two successful Danish dramas. Then came Häxan.

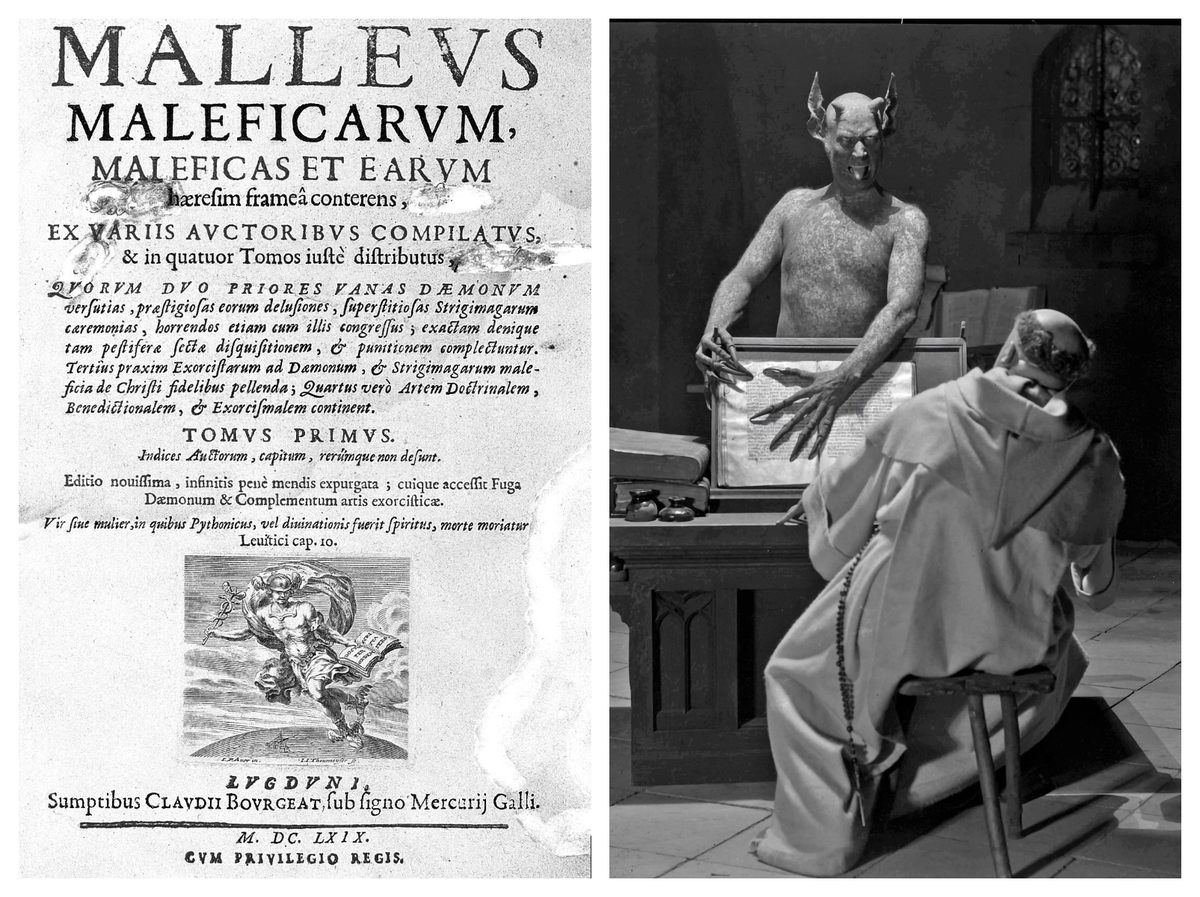

According to the popular narrative that has evolved around the film, Christensen became obsessed with witchcraft after stumbling upon a copy of the Malleus Maleficarum, a notorious 15th-century witch-hunting manual. Given his education, he was likely already familiar with contemporary psychoanalysis of the occult. The Malleus Maleficarum just made for a better origin story. Christensen was always “myth-making about himself,” says McGill University professor and Realizing the Witch coauthor Todd Meyers. “The movie itself has a kind of salesmanship to it.”

We see evidence of this persuasive confidence onscreen, as Christensen gazes sternly into the camera during Häxan’s introduction. Later, in the role of Satan, he leers at the audience in prosthetic horns. Throughout the film, there is an amusing contrast between Christensen’s lofty academic goals and the film’s more salacious scenes. Sex sells.

Christensen’s salesmanship may also explain how he secured funding for such a bizarre project. In 1919 the Danish film industry’s censorship guidelines discouraged dark or blasphemous topics, so he approached the Swedish company Svensk Filmindustri. It funded an ambitious three-year shoot, which was virtually unprecedented, according to film scholar Vito Adriaensens.

“A month would be a long time to spend shooting a feature,” says Adriaensens, who is writing a book about Häxan. “Some of them were made in weeks.”

Christensen also hired non-professional actors—he wanted his medieval peasants to look as authentic as possible. He apparently succeeded. Decisions such as casting an elderly flower seller as the film’s most prominent witch generated buzz in the Scandinavian press. As Adriaensens puts it, “You could read the history in the grooves of her face.” Not a typical movie star, but undeniably marketable.

In English-language media, Häxan’s coverage was focused more on its weirdness and shocking scenes. Indeed, Variety labeled it “absolutely unfit for public exhibition” in 1923.

A heavily edited American rerelease continued this narrative in the 1960s, playing at late-night screenings with narration from counterculture icon William S. Burroughs. Yet Häxan’s subversive reputation may say more about American puritanism than it does about the movie itself.

Early American film censors were influenced by the same kind of conservative Christian groups that would shape the Hays Code of the 1930s and the Satanic Panic of the 1980s. In turn, its history as a banned film potentially helped Häxan catch on among horror fans. But back in Denmark and Sweden, Häxan wasn’t quite as scandalous.

“There was a genuine interest in the scientific aspects of it,” Adriaensens says, noting that Christensen’s research was praised by contemporary intellectuals.

Thanks to Häxan’s buzz, Christensen joined the flood of European filmmakers moving to Hollywood. After making seven movies there (including some horror flicks capitalizing on Häxan’s notoriety) he returned to Denmark, eventually directing four more features. Far from being forgotten, Häxan received a respected Danish rerelease in 1941

In recent years Häxan has enjoyed an uptick in live screenings, and was celebrated by horror audiences and silent film buffs during its 100th anniversary in 2022.

Yet despite its influence on horror filmmakers such as Robert Eggers (The Witch), Häxan isn’t really a horror movie. Nor is it a typical documentary. If anything, Christensen’s dramatic storytelling is too effective, overshadowing his academic arguments about witchcraft and mental illness. And as he invites us to examine the nature of the witch, we can’t help but psychoanalyze Christensen’s own creative goals. The filmmaker presented himself as a rigorous academic, but also donned the horns of Satan onscreen, beckoning slyly to his audience as he luxuriated in the grotesque.