Once a cryptid captures the popular imagination, sooner or later it’s going to enter the realm of children’s stories. Part of it is the natural inclination to educate the young. And part is the tendency in our culture to relegate the magical and the out-of-the-ordinary to minds considered immature or unformed. Adult minds, in that view of the world, know what’s real and what’s not.

Genre fans of course know better. We also know that works supposedly intended for children can be wonderfully subversive and subtly complex. The child reader or viewer may not get all the layers, but as they grow, so will their understanding.

The Bunyip is first of all an indigenous story, a creature of many forms and meanings. The arrival of European colonists added their cultural viewpoint to the mix. Its name came to mean something darker, closer to the English devil. It also gained the connotation of fraud or hoax. A bunyip can be a spirit, a cryptid, or a practical joke analogous to the North American jackalope.

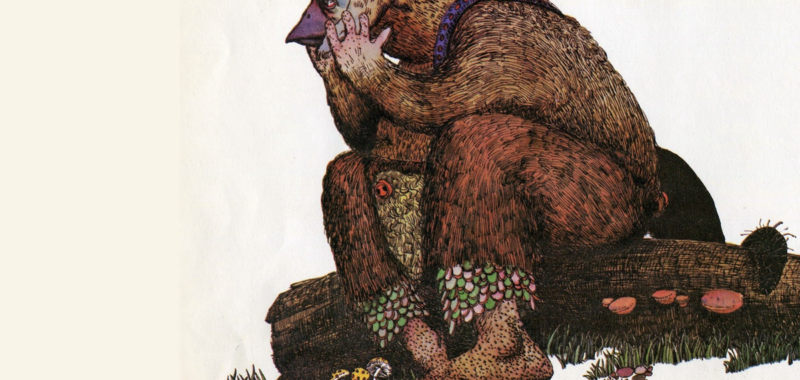

There are a good number of Bunyip books for children. One of the better-known titles is Jenny Wagner’s The Bunyip of Berkeley’s Creek (1974). It’s a picture book, beautifully illustrated by Ron Brooks, and its story is deceptively simple.

A creature emerges from a billabong “for no particular reason” (because what does reason have to do with a cryptid after all?), terrifying the local fauna. It’s large, it’s covered in mud, and it does not know what it is. Since it’s night, everything is asleep; it can’t press them for answers.

In the morning, a passing platypus tells it what it needs to know. It’s a Bunyip.

But that only leads to more questions. What does it look like? Is it handsome?

Every creature he asks (because he quickly achieves gender) either departs at speed or declares that he’s horrible. Horrible feathers, says a wallaby, which is a furred mammal, and horrible webbed feet. Horrible fur and a horrible tail, says an emu, which is a bird with feathers. And then he asks a man, who declares that he looks like nothing at all. He doesn’t exist.

Whatever creature the Bunyip asks, its answer is the opposite of what the creature finds desirable. The Bunyip keeps wanting to know if he’s handsome; if he’s attractive. He wants that assurance. The man’s assertion of his nonexistence devastates him, and drives him back to his billabong, where he gathers his belongings and sets off on a quest.

This form of the Bunyip recalls the speculation that some of the sightings in the nineteenth century may have been swagmen hiding from the law. Swagmen carried huge packs and camped by watercourses, and would duck into the water when pursued. A swagman emerging from a billabong would look like a Bunyip manifesting out of water and mud.

Our Bunyip finds another billabong, where nothing will see him (or judge him) and where he can be “as handsome as I like.” He makes camp there, swagman style, and settles in.

In the night, “for no particular reason,” the waters of the billabong stir, and a large, mud-covered form emerges. It too wonders what it is, but the Bunyip is delighted to have an answer. When she asks what she looks like, he says happily, “You look just like me.” And he has a mirror to prove it.

The lesson seems to be that beauty is in the eye of the beholder, and that every creature needs to be beautiful to itself. The horror of the devil-Bunyip is entirely in the observer’s mind, and so is the possibility that it doesn’t exist at all. Fortunately for the Bunyip in the story, not only does it exist; there’s more than one of it, and we can presume, from the fact that the second one is a she, that in time there will be more.

That’s a happy ending, if a little dark around the edges.

Hector’s Bunyip (1986) is a short film at 59 minutes, but it makes every minute count. It’s heartwarming and wholesome and just what I need after a hard week.

Six-year-old Hector is a foster child in a big, happy, messy Australian farm family. As his foster father puts it, “We had three kids of our own, but they just didn’t seem to be enough. So we opened our home to three more.”

All three are difficult placements in Australia in the 1980s. Lim is Asian, Michael is Indigenous, and Hector has a disability: one leg is in a brace. Parents George and Irene Bailey (shades of It’s a Wonderful Life) and offspring Herakles, Cassandra, and Pandora accept the three boys without reservation.

George is not a good farmer. His passion is inventing gadgets using odds and ends and salvaged parts from anywhere and everywhere. He’s rigged a lift, which is the coolest thing ever, so that Hector can get up to the loft where the boys sleep without having to negotiate the ladder, and he’s working on a major new project, a mechanical mousetrap for large-scale pest control.

Unfortunately George’s gadgets are not bringing in income. The farm is in trouble, and the council is coming after it for nonpayment of fees. The head of the council, Ernest Slater, who happens to be in real estate, has what he considers the perfect solution: the Baileys can sell the farm for what in the US we would call back taxes.

When George and Irene refuse, he gets nasty. He calls in Child Welfare Services to break up the family. Ms. Tremball is stern, humorless, and by the book, and she determines that while Michael and Lim are coping well with the family’s cheerful chaos, Hector is not.

Some of this has to do with his disability, but it doesn’t help that he has a large (apparently) imaginary friend. Bunyip appears at the beginning after a successful prank the Bailey kids have played on Slater’s obnoxious son. Hector gets left behind when the others bolt for home; his leg won’t let him keep up, and he’s stranded beside the billabong.

There, he tells his siblings, he meets and befriends Bunyip. The other kids take this in stride. They can’t see it, but they accept that it’s there. So do their parents, who do what wise parents of kids with imaginary friends do: they leave space for Bunyip at the dinner table, and allow for its presence however Hector needs them to.

Bunyip is too big to sleep in the loft, but Michael points out that a Bunyip’s bed is in his billabong. (Michael knows about Bunyips. Not because he’s Indigenous, but because he wrote a paper for school. Fifty-plus pages.) When Hector goes to bed, he asks his mom to let the Bunyip out. She’s busy, she nods, whatever.

Out of nowhere, the outside door shuts on its own. She and her daughter exchange glances. Can’t be. Can it?

When Ms. Tremball arrives, the Baileys are on their very best behavior, putting on a show for the government inspector. Unfortunately, part of the show involves banishing Bunyip outdoors for the duration of the visit. Hector is in tears over it, and unburdens himself to Ms. Tremball, who gets it all wrong.

She thinks Bunyip is a stuffed toy, and she’s mildly appalled that Hector makes it “sleep” in the billabong. She’s even more appalled by his floods of tears. She mistakes his tantrum over Bunyip’s banishment for unhappiness with his family situation. He has to be removed, for his own good.

The Baileys come up with a plan. They hide Hector and claim that he’s disappeared. They let it be understood that Bunyip has abducted him.

The case becomes an international sensation. The whole world is riveted by the search for the boy and the Bunyip, and they’re all up in arms over the attempt to lock him up in an institution. In very short order, people start arriving, looking for the Bunyip.

It quickly dawns on Slater that this is a golden opportunity. All those beautiful tourist dollars are pouring into the town, and he’s right there at the source.

George meanwhile is seeing a distinct uptick in his fortunes. Not only does Slater cut a deal with him to waive the money he owes the council, but a gallery owner shows up, having seen George’s gadgets in the background of the news footage. It’s Art! It’s amazing! He can sell it!

Hector has to stay in hiding, though both he and Bunyip are seriously unhappy about it, because his case is mired in bureaucracy. The paperwork has been filed. He’s going to be removed. There’s no way to stop it.

Miracles do happen, and friends in high places are very useful to have. All’s well that ends well, with a little bit of sadness, and one last prank to round it off.

Since Bunyip is (presumably) imaginary, we have to go by what Hector says, with some input from Michael. He’s as tall as a tall man, and too massive to manage the lift or the ladder to the loft, though Michael opines that he fits up there just fine. He just prefers to sleep in the billabong.

Michael also says that Bunyips have scales, but according to Hector, this Bunyip does not. He’s been on land too long, says Michael; that’s how you tell.

Bunyip has a tail, and it’s an indicator of his mood. The sadder it is, the straighter it gets. Hector asks George to make a gadget to help, a bunyip tail curler. George is on board with that, because he’s a good dad.

It seems that Bunyips lay eggs. Or maybe that’s another prank. We can’t really know for sure.

Nor can we know if Bunyip really is imaginary. There’s the door, that first night. There are certain angles to the shadows when people are talking to Bunyip. The water in the billabong swirls just so, when it might be closing over Bunyip’s head. And Bunyip loves scones, and first they’re on the bank of the creek where Hector left them, then they’re not.

Hector believes. His family goes along with it, and uses it for their own purposes. It’s a nice riff on the idea of the bunyip as a hoax or a prank, but with undertones of actual magical creature. In the end, it’s exactly as real as we want it to be.