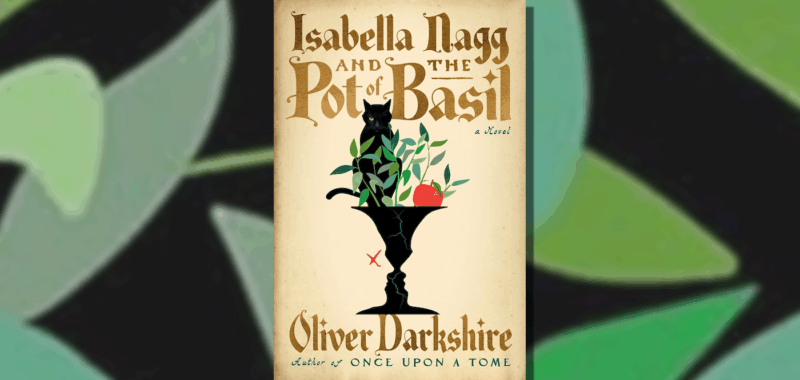

We’re thrilled to share an excerpt from Isabella Nagg and the Pot of Basil by Oliver Darkshire, a cozy fantasy reimagining a heroine of Boccaccio’s Decameron in a delightfully deranged world of talking plants, walking corpses, sentient animals, and shape-shifting sorcerers—out from W. W. Norton & Company on May 13th.

In a tiny farm on the edge of the miserable village of East Grasby, Isabella Nagg is trying to get on with her tiny, miserable existence. Dividing her time between tolerating her feckless husband, caring for the farm’s strange animals, cooking up “scrunge,” and crooning over her treasured pot of basil, Isabella can’t help but think that there might be something more to life. When Mr. Nagg returns home with a spell book purloined from the local wizard, she thinks: what harm could a little magic do?

PROLOGUE

It was late summer under a pale green sky, and the wizard Bagdemagus had decided to retire. Not right now, perhaps in a decade or two, when the ache in his bones had really settled in. He felt the itch, the same way he’d felt it when he’d first picked up the book of practical magic commonly known amongst wizards as the Household Gramayre. He hadn’t known that strange, subtle itch for what it was, back then. Now he could recognize it as a sign that it was time for something new. Wizards didn’t die of old age. They were too suffused with Gramayre for that. No, a wizard changed. They took on new shapes, new forms, until one day you never returned. It was in their nature, just as the sun was pushed across the sky by a gigantic beetle, and as goblins returned to the valley each year at the first mischievous whisper of autumn.

The valley was tucked away below the village of East Grasby, and Bagdemagus wandered it freely, deep in the heart of the crag that would soon blossom with wild goblins and their treacherous fruits. He’d tried to banish the goblins for good, when he’d first come into his power, but some magics were too old and buried too deep. Instead, when all power and works had failed him, he’d reluctantly done exactly what his wizardly predecessor had done, and contained the problem instead. A spell encircling the valley, fencing the goblins inside to ensure neither they nor their enticing wares could work evil in East Grasby1. The goblins were harmless enough as long as they stayed in their market until winter, when the cold caused them to wither away.

As he walked, and with extreme care, he scattered mandrake leaves behind him. Most people didn’t know of the mandrake’s special properties, because they didn’t care to listen to the old folk tales. The people of East Grasby didn’t listen much to anyone. To each other. To their surroundings. To any of the lectures he gave on the matter when someone turned up at his door with mandrake poisoning. As a matter of principle, and professional curiosity, Bagdemagus listened all the time. There wasn’t much else to do when you kept your own company, unless you counted the grimalkin, which Bagdemagus didn’t. He spent so much time with the feline creature that he almost considered it part of him, much in the same way as the Household Gramayre. Spells and memories all folded into each other until you couldn’t tell which was which anymore. It was going to be hard to leave it all behind.

It was often the case that Bagdemagus became so caught up in his own inner dialogue that he failed to notice what was right in front of him, and today was no different. Gaze turned firmly inwards, he stumbled across something heavy in front of him. Catching his balance, he stepped back onto the mandrake leaves, scuffing the line. Cursing blithely, he turned to see what had tripped him.

The body was headless. Large, strong, and oddly contorted, as if it had died in some distress. Unfazed by the sight (Bagdemagus was old, older than anyone gave him credit for), he warily reached down to assess the state of decay. Less than a day old, perhaps killed the previous evening. He couldn’t state the exact cause of death, not without opening the Gramayre, and there were spells in the books that even he feared to cast. What worried him most was the fact that it had been left unwatched. Having been abandoned without a vigil or burial rites, the corpse was almost certain to wake as a licce, tirelessly seeking out some last vengeance or obsession. A body didn’t need a head to be dangerous.

He inspected the wound. Jagged. Clumsy. The head had been severed in a hurry, or by someone unfamiliar with the workings of the body. A murder, then. It wasn’t the first one in East Grasby and it wouldn’t be the last2.

The grimalkin sidled out from behind a rock, all extra toes and crooked teeth. It looked nothing like a cat in any meaningful sense, but that was still the closest word one could use to describe it. The creature was something like an assistant, a deputy librarian, and a tutor all rolled into one. The grimalkin liked to nap on a particular rock when Bagdemagus did the goblin-mandrake ritual, because it was an excellent sunbathing spot, and they rarely ventured down into the valley together except to perform this specific rite.

Buy the Book

Isabella Nagg and the Pot of Basil

“Gosh,” the grimalkin said, dryly, indicating the body. “Well, it’s not goblin. I suppose that’s a mercy.” It sniffed the corpse. “Not watched. It’s going to turn. We’ll have a licce on our hands before sundown.”

Bagdemagus sighed. “Have to do everything myself,” he grumbled. As if he’d have accepted help from anyone, which he would not have.

Reaching into the depths of his mind, where the spells he had memorized that morning were drifting about, he sifted through the jumble of words and incantations until he came across a spell of burning. It was an unruly thing. Fire always was. It wanted to escape, and you had to be wary lest it catch onto something inside you and burn you out from the middle. With the spell on his lips, eyes burning like coals, he made to touch the body.

“What on earth are you doing?” The grimalkin’s sour voice cut into his concentration. He paused.

“What does it look like? I’m burning it before it gets up again.”

“We don’t have the whole body.” The cat had that superior expression it leveraged whenever he knew something the wizard didn’t. This happened often.

“What difference does it make?” He was irritable now. The spell slipped from his grasp and vanished from his mind. Bagdemagus wondered, briefly, where it went3.

“If you don’t burn the whole thing,” said the grimalkin, “particularly the head, you won’t kill it. You’ll just end up with some very alive bones, unless you have fire hot enough to burn those too. Which you don’t. Because I know all your spells.” Smugly, it waved its tail. “You’ll have to bury it until we find the head, and then we can get rid of it all at once.”

Sighing loudly enough to make a point, Bagdemagus delved for another spell. This time, slumbering under some cobwebs, and next to where he’d left his list of favourite celery memories, was the Cant of Terrestrial Gerrymandering. He retrieved it. It had been a while since he’d memorized it, but it was still good. Under his careful guidance, the spell worked the same way it always did, opening a sizeable pit in the earth into which a body (or several bodies, if you squeezed them) could be placed. With a kick, he heaved the dead man into the newly formed grave. Six feet under, that was the key. Licce might be strong, but even they struggled to reach the surface from there.

“I suppose we should find the head,” he said, “before it gets into trouble.” He looked around, but it wasn’t anywhere in sight.

“Seems someone made off with it,” said the grimalkin. “Or it rolled away. Either way, we’ll be at this all day. We don’t even know which way to start off in.”

“We could ask the tinderbox,” said Bagdemagus, idly. “We only used two questions, remember?”

“Absolutely not,” the cat said, firmly. “Stop suggesting that. I lost an eye last time, Bagsy, in case you forgot.”

“Alright, alright. You keep looking after it for me, then.” He scratched the famulus around the ears.

Standing up properly, he pulled up his trousers, which were always falling down just a little. “We’ll look for the head later,” he told the cat, which helped to scoop the dirt back into the grave. “It can’t have gone far. And the rest of the corpse is safe down there. No one comes here, and no one would be stupid enough to dig in the goblin market, not unless they want to be weeviled.” He sounded almost wistful. He hadn’t turned anyone into a weevil in years.

“Can we stop at the river?” The cat seemed to have brightened in mood now that the body was gone. “You know the one. I want a fish. Then maybe some witch backgammon4?”

The river. That would be nice. He could sit down for a while, rest his back (which had developed an ungodly twinge from all those nights under the stars). Finding this head could wait, it was of little urgency now. Besides, a licce didn’t speak. A head could cause little trouble on its own, unless it bit someone and they got gangrene. He finished scattering the mandrake leaves and picked up his bags.

Yes, a sit-down. Some nice fish. And then, in a few short decades, he would retire.

He was halfway down the path when all thought of the rogue head slipped from his memory altogether.

Twenty years passed before Bagdemagus decided to finally retire. In that time he never quite got around to remembering the headless body, buried six feet under the ground in the goblin valley.

Deep below the earth, dead muscles twitched.

Excerpted from Isabella Nagg and the Pot of Basil, copyright © 2025 by Oliver Darkshire.