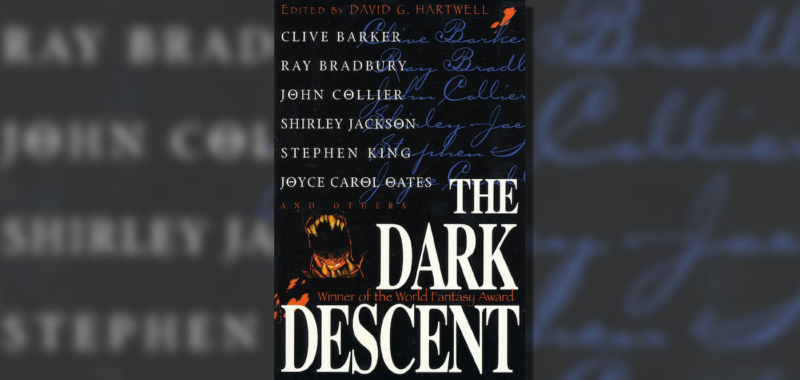

Welcome back to Dissecting The Dark Descent, where we lovingly delve into the guts of David Hartwell’s seminal 1987 anthology story by story, and in the process, explore the underpinnings of a genre we all love. For an in-depth introduction, here’s the intro post.

“Schalken the Painter” is perhaps one of Le Fanu’s best works. Inspired by the paintings of Gottfried Schalcken and Gerrit Dou, two Dutch masters known for their candlelight portraits and ability to capture the unnerving play of light and shadow, Le Fanu used their paintings’ dreamlike qualities and familiar gothic tropes, crafting a story of nightmare logic and intense visuals so striking that the BBC even adapted it into a TV movie with cinematography based on the actual painters’ work (even if I think Le Fanu’s description sounds more like King James from Atun-Shei’s Daemonologie.) While blending history, nightmare, and the grotesque is nothing new for Le Fanu, “Schalken the Painter” puts its own spin on the usual “damsel in distress” plot, crafting a twisted story of power and powerlessness wielded by a creature from beyond the grave.

A painter named Godfrey Schalken is apprenticed to a Dutch master painter by the name of Gerard Douw. Schalken is a poor man, but good-hearted, happy to spend his company in Douw’s studio and in the company of Douw’s bewitching ward Rose. Rose and Schalken spend their days conversing and while he falls harder for her than she for him, they both find themselves enamored. Sadly for the pair, Vanderhausen, a rich man with a shadowy past and a monstrous appearance, arrives unannounced with a massive dowry and plans to provide for Rose for the rest of her life. Swayed by the outrageous fortune on offer, Douw eagerly agrees to Vanderhausen’s demands. When the pair vanishes without a trace (and all traces of Vanderhausen with them), only for Rose to reappear in the midst of a breakdown, it falls to Schalken and Douw to piece together what happened and save Rose before her monstrous husband comes to collect her.

The problem in “Schalken the Painter” isn’t that no one in the story can stop Vanderhausen, it’s that they have no idea that they can. From the very start, Vanderhausen projects the image of immense wealth and power, enough to overwhelm Schalken and Douw when he first demands Rose’s hand in marriage. Douw manages to put up token resistance to Vanderhausen, only to be immediately rebuffed by the massive dowry. They know things are wrong with the situation, especially when they see Vanderhausen in full view for the first time, but their systems of class and prescribed behavior favors their mysterious guest. While Schalken and Douw are at least respectable, they respond the way they’re supposed to when confronted with one of their “betters,” despite their misgivings. While the point is blunt, especially considering an undead monster is literally buying an innocent woman, at the same time, it’s clear the structures of wealth and power are protecting the inhuman Vanderhausen.

Wealth and power also play a role in why none of the protagonists (it would be a huge stretch to call anyone in this story a “hero”—Schalken is a “nice guy” and terminally passive; Douw sells his surrogate daughter for a truckload of cash) could have resisted even if they wanted to. A major way those with wealth and power maintain their grip on the rest of us is through two key methods. First, they simply act like the possibility someone would tell them “No” doesn’t exist. The second and more insidious method is that they play on the possibility that saying “no” to them would come with negative—even horrifying—consequences. In the case of “Schalken the Painter,” the appearance of Vanderhausen is enough to spark the imagination of what would happen if anyone opposed him. Surely enough, when Vanderhausen is momentarily thwarted, it doesn’t end particularly well for anyone.

If there’s anything to indict Schalken and Douw, it’s those moments immediately after Rose’s escape and return to Douw’s home. Even then, it’s already too late for anyone in the story. Despite Rose having escaped Vanderhausen’s clutches, it’s clear at this point (especially to the reader) that they’re dealing with something horrifying and inhuman. Once again, Rose is doomed by the status quo: when confronted with a woman terrified to the point of insensibility, Douw assumes she’s suffered a psychotic break and takes none of her warnings seriously. Treating the situation like any other mundane circumstance under the corrupt status quo, Douw acts rationally. The events of “Schalken the Painter” are not, however, mundane. In the same way Vanderhausen uses his power, privilege, and unspoken threats to secure his purchase of Rose, he also uses the men’s insistence on the familar mundane (and misogynist) system to kidnap her back and claim her as his own. Despite Rose’s insistence that she should not be left alone, Douw does exactly that…and in that moment, Vanderhausen strikes and carries her away.

While Douw and Schalken are certainly culpable—their complete inability to do anything even remotely to stop Vanderhausen is enough to indict them—it’s also clear they have no conception of how they’d even try. From the reader’s standpoint, it seems so simple to imagine that if they’d said no at any point, they might have had a chance, but according to the corrupt system that governs their lives and behavior, both behaved rationally, and the combination of Vanderhausen’s understanding of the rules and unwillingness to play by them makes the two men his accomplices. The idea of standing in opposition to monsters like Vanderhausen is simply not something average people are usually able to see themselves doing. Even when Douw is displeased by the situation, he goes along with it anyway because he wants to believe that what’s going on is in some way normal, and if it wasn’t, something would be there to stop it. It never occurs to him—as it wouldn’t for many people living under oppressive circumstances—that the moral judge he’s waiting for is in fact himself.

This makes “Schalken” similar to “Mr. Justice Harbottle,” our earlier exploration of J.S. Le Fanu. Both stories detail how corrupt men abuse the system for their own gain and reward, and where even the most well-intentioned abuses of power are still monstrous. The difference is that “Schalken” is outright grim and cynical. No one saves Rose from her betrothed. No one even resists, because (in a similar manner to other works in this volume) on some level they believe in things being “correct” even despite their compunctions. The horror in Le Fanu’s stories is the acceptance (or outright abuse) of a moral universe designed to profit the privileged and inhuman monsters willing to exploit it. “Harbottle” allows us the catharsis of a moral universe; “Schalken” denies that distance.

This is the conceit of “Schalken the Painter,” that in depicting a universe where a dark and monstrous figure is allowed to profit from sin, privilege, and exploitation of systemic norms, the reader themselves must therefore indict and act as ultimate judge of the characters. The horror they feel at the protagonists’ compliance in Rose’s fate is both meant to terrify and act as a challenge, a way for Le Fanu to show them the horrors of the world they inhabit, guiding them to an understanding of how terrifying complicity in that world truly is.

And now to turn it over to you. Is Le Fanu’s metaphor well-used, or is a monster buying a woman from her hapless father figure a trifle blunt? What’s your favorite painting-based horror story?

And please join us next time as we tackle feminist horror icon Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s subversive take on “hysterical fiction” with “The Yellow Wallpaper.”