This year’s presidential election is incredibly close, with a recent report describing the margins as “razor thin” in key swing states, with a fraction of a point separating former President Donald Trump and Vice President Harris in the polling averages.

Despite the fact that the last nine presidential elections have been close and voter turnout continues to grow, around one-third of the voting-eligible population still did not vote in the 2020 presidential election. More than 50 percent did not vote in the 2022 midterm election.

While myriad techniques from behavioral science and beyond have been used in the past to help increase voter turnout, we propose four underutilized techniques to flip the script and drive people to the polls.

Despite its increasing popularity, early voting is an option that is currently under-utilized in campaign efforts. Instead of the government dictating what day you need to show up at the polls, consider voting early as having control over when voting fits best into your own schedule. People often think narrowly, focusing only on Election Day as Tuesday, Nov. 5, but reinforcing voting on your own time can give a greater sense of control.

For any given task, we often feel that we will have more time to complete that task in the future, and yet when tomorrow becomes today, we are surprised to find that we are just as busy. This idea, known in behavioral science as slack theory, implies that we should go ahead and go to the polls now to vote.

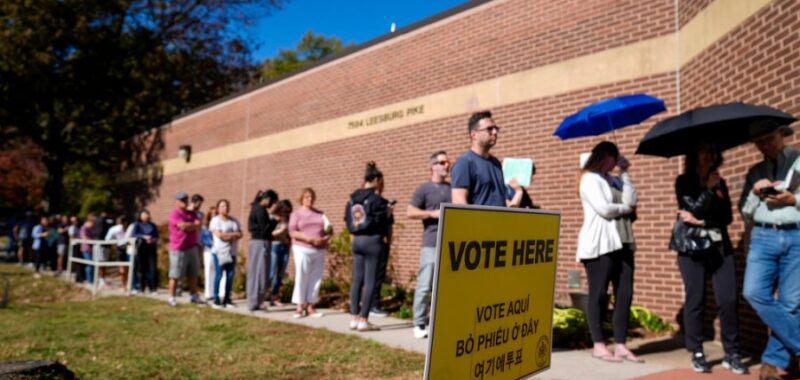

Waiting until Election Day will bring new unexpected reasons not to get around to voting: a dentist appointment, a sick child, meetings that run late, etc. By avoiding this friction at the onset and focusing planning efforts around early voting, we can also help minimize lines and wait times on Nov. 5, which serves to make voting on Election Day more desirable for those who do wait.

In fact, voting early is increasingly becoming a social norm, with record-breaking early voting already taking place in several states for the 2024 presidential election. This presents an opportunity to focus immediate campaign efforts around this momentum to get people to the polls now — not just on Election Day.

Our perceptions of the world are important drivers of behavior, whether or not these perceptions are accurate. One perception that inhibits voting is that a single vote won’t make a difference. While media outlets, like The New York Times, emphasize how a few votes can swing the 2024 presidential election — maybe even fewer people than a college football stadium holds — this messaging may not resonate for people who know which way their state swings. Attempts to change perceptions through information often fail, as we tend to process information through a lens that reinforces our own existing perceptions.

Instead, the value of voting can be reframed from deciding an election to gaining visibility with policy makers, as we know that politicians pay attention to people who show up at the polls. Casting a vote signals, “I belong to a group that shows up and deserves attention,” and this becomes a way to ensure that elected officials and policymakers take notice of your community, which can give individuals a lasting voice with those in office.

Rather than only focusing on the positive outcomes of voting, research shows that emphasizing what is lost by not voting can be more effective, as losses often hurt more than equivalent gains. For example, when funding for a library in Michigan was at risk, local leaders didn’t just highlight the benefits of keeping the library open, which was not particularly moving for the community. Instead, they asked the community to imagine life without the library.

The campaign did this in a vivid way through a faux campaign to burn books, which incited anger and upset amid the community. After community voices became active, they revealed the true purpose of the campaign: a vote against the library is like a vote to burn books. This successful campaign led to preservation of the necessary funds to keep the library open. Similarly, we can reframe the benefit of voting by what it means not to vote. For example, not voting means handing over control to other voters.

Research shows that people often fail to consider the costs of not pursuing a particular option. So, when it comes to voting, we may think a lot about the time it takes to stand in line at the polls without considering the negative outcomes associated with not voting. Reframing the time it takes people to vote around the costs of not voting could potentially have a powerful effect on their voting behavior. Thirty minutes to an hour may feel like a long time to spend at the polls but visualize this within the context of the next four years; spending 30 minutes to speak up now is a lot more powerful than trying to fight the policies of a candidate you dislike over the next four years.

In voter engagement messaging, there’s a natural tendency to emphasize the importance of voting: it’s our civic duty, a national privilege, the language of democracy. However, research on motivation shows that making an experience enjoyable or rewarding is often more effective than emphasizing importance. For example, motivating exercise is best achieved by getting people to have fun versus telling them how much it impacts one’s health.

The same approach should be applied to voting. Some brands have tried to make voting fun by offering free donuts, discounted drinks and massages for those who vote. The real opportunity lies not in individual perks but in the integration of these perks with the voting experience. For example, consider offering an assembled goodie bag or hosting a bring-a-friend campaign that encourages voters to come together to receive a reward.

While some individual states have had long-held limitations on what can be distributed, by where and by whom, it is worth expanding the discussion around the civic benefits of having bipartisan organizations not only make lines endurable, but also make them fun.

While efforts to increase voter turnout face numerous challenges, there are still some underutilized strategies based on deep human understanding that can be employed over the next few days to drive people to the polls. As we approach this critical election, the real question remains: will the next four years be shaped by the voice of Americans or will it be shaped instead by inertia and inaction?

Ravi Dhar is the George Rogers Clark Professor of Management and Marketing at the Yale School of Management and is director of the Yale Center for Customer Insights. Jennie Liu is a lecturer in the Practice of Management at the Yale School of Management and is the executive director at the Yale Center for Customer Insights. Nathan Novemsky is professor of marketing in the Yale School of Management and is member of the Yale Center for Customer Insights.